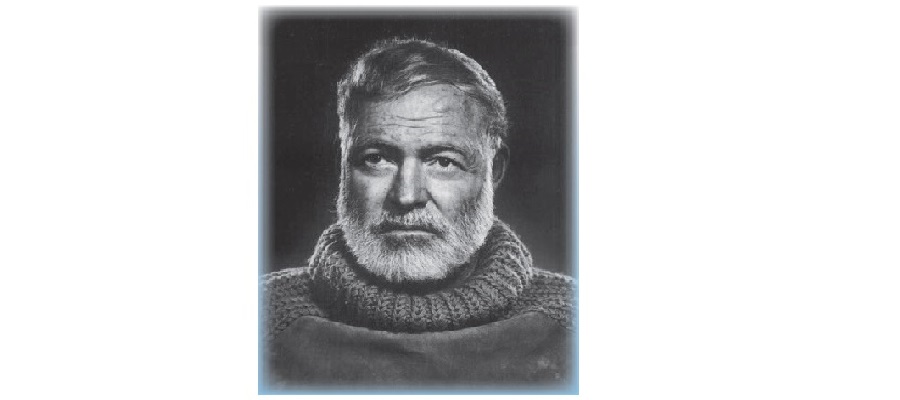

Ernest Hemingway’s novella The Old Man and the Sea was published on September 1, 1952. One of his most famous works, it centers upon Santiago, an aging Cuban fisherman who ventures1 far out in the Gulf Stream to prove his abilities and to break his 84 days of bad luck.

On the first day a big fish takes his bait2. Unable to pull in the great marlin3, Santiago instead finds the fish pulling his little boat. Two days and two nights pass in this manner, during which the old man bears the tension of the line4 with his body. Though he is wounded5 by the struggle and in pain, Santiago expresses a compassionate appreciation for his adversary6. On the third day of the ordeal7, the fish begins to circle the boat, indicating his tiredness to the old man. Santiago, now completely worn out and almost in delirium, uses all of his strength to pull the fish onto its side and stab the marlin with a harpoon8, thus ending the long battle. While Santiago continues back to the shore, sharks are attracted to the trail9 of blood left by the marlin in the water. They have almost devoured the marlin’s entire carcass10, leaving a skeleton consisting mostly of its backbone, its tail and its head. Finally reaching the shore, Santiago struggles on the way to his shack11, carrying the heavy mast12 on his shoulder. Once home, he lies onto his bed and falls into a deep sleep. He dreams of his youth and lions.

The Old Man and the Sea was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1953. Many critics favorably compared it with such works as William Faulkner’s The Bear and Herman Melville’s Moby Dick.

Hemingway, himself a great sportsman, liked to portray soldiers, hunters, bullfighters as tough, at times primitive people, whose courage and honesty are set against the brutal ways of modern society, and who in this confrontation lose hope and faith. His straightforward prose, his spare dialogue, and his fondness for understatement are particularly effective in his short stories.

Extract:

“How do you feel, fish?” he asked aloud. “I feel good and my left hand is better and I have food for a night and a day. Pull the boat, fish.”

He did not truly feel good because the pain from the cord13 across his back had almost passed pain and gone into a dullness14 that he mistrusted. But I have had worse things than that, he thought. My hand is only cut a little and the cramp15 is gone from the other. My legs are all right. Also now I have gained on him in the question of sustenance16. It was dark now as it becomes dark quickly after the sun sets in September. He lay against the worn wood of the boat and rested all that he could. The first stars were out. He did not know the name of Rigel but he saw it and knew soon they would all be out and he would have all his distant friends. “The fish is my friend too,” he said aloud. “I have never seen or heard of such a fish. But I must kill him. I am glad we do not have to try to kill the stars.”

Imagine if each day a man must try to kill the moon, he thought. The moon runs away. But imagine if a man each day should have to try to kill the sun? We were born lucky, he thought.

Then he was sorry for the great fi sh that had nothing to eat and his determination to kill him never relaxed in his sorrow for him. How many people will he feed, he thought. But are they worthy to eat him? No, of course not. There is no one worthy of eating him from the manner of his behaviour and his great dignity.

I do not understand these things, he thought. But it is good that we do not have to try to kill the sun or the moon or the stars. It is enough to live on the sea and kill our true brothers. Now, he thought, I must think about the drag17. It has its perils and its merits18. I may lose so much line that I will lose him, if he makes his eff ort and the drag made by the oars is in place and the boat loses all her lightness. Her lightness prolongs both our suff ering but it is my safety since he has great speed that he has never yet employed. No matter what passes I must gut19 the dolphin so he does not spoil and eat some of him to be strong.

Now I will rest an hour more and feel that he is solid and steady before I move back to the stern20 to do the work and make the decision. In the meantime I can see how he acts and if he shows any changes. The oars are a good trick; but it has reached the time to play for safety. He is much fish still and I saw that the hook was in the corner of his mouth and he has kept his mouth tight shut. The punishment of the hook is nothing. The punishment of hunger, and that he is against something that he does not comprehend, is everything. Rest now, old man, and let him work until your next duty comes.

He rested for what he believed to be two hours. The moon did not rise now until late and he had no way of judging the time. Nor was he really resting except comparatively. He was still bearing the pull of the fish across his shoulders but he placed his left hand on the gunwale21 of the bow and confided more and more of the resistance to the fi sh to the skiff itself.

How simple it would be if I could make the line fast, he thought. But with one small lurch22 he could break it. I must cushion23 the pull of the line with my body and at all times be ready to give line with both hands.

“But you have not slept yet, old man,” he said aloud. “It is half a day and a night and now another day and you have not slept. You must devise a way so that you sleep a little if he is quiet and steady. If you do not sleep you might become unclear in the head.” I’m clear enough in the head, he thought.

Too clear. I am as clear as the stars that are my brothers. Still I must sleep. They sleep and the moon and the sun sleep and even the ocean sleeps sometimes on certain days when there is no current and a flat calm.

But remember to sleep, he thought. Make yourself do it and devise some simple and sure way about the lines. Now go back and prepare the dolphin. It is too dangerous to rig the oars24 as a drag if you must sleep. I could go without sleeping, he told himself. But it would be too dangerous.

He started to work his way back to the stern on his hands and knees, being careful not to jerk against the fish. He may be half asleep himself, he thought. But I do not want him to rest. He must pull until he dies.

Janka Něničková

VOCABULARY: 1odvážiť sa – trúfnuť si – odvážit se, troufnout si; 2návnada; 3druh veľkej morskej ryby – druh veliké mořské ryby; 4znášať napätie lanka – snášet napětí lanka; 5/wu:ndid/ ranený – raněný; 6/ædv∂s∂ri/ protivník, sok; 7/o:di:l/ utrpenie, tvrdá skúška – utrpení, tvrdá zkouška; 8vraziť harpúnu do ryby – vrazit harpunu do ryby; 9stopa; 10zožrali celú mŕtvu rybu – sežrali celou mrtvou rybu; 11chatrč; 12sťažeň – stěžeň; 13lanko; 14otupenosť – otupělost; 15krč – křeč; 16výdrž; 17vlečenie – vlečení; 18/per∂l/ riziko a prednosti – riziko a přednosti; 19vyvrhnúť vnútornosti – vyvrhnout vnitřnosti; 20zadná časť lode, korma – záď; 21okraj; 22prudké naklonenie – prudké naklonění; 23zmierniť – zmírnit; 24provizórne zmontovať veslá – provizorně smontovat vesla